What is the atomic number of hassium?

107

108

109

110

The enigmatic world of Hassium, a synthetic marvel in the periodic table, through our comprehensive guide. Delving into the essence of Hassium, this section unfolds its creation, characteristics, and scientific significance. With expert insights and illustrative examples, we illuminate Hassium’s place in nuclear chemistry and its parallelism with other group 8 elements. Our guide is designed to satisfy curiosity, enhance knowledge, and present Hassium in a new light, making it a pivotal resource for enthusiasts and scholars alike. Engage with the fascinating narrative of Hassium, and unlock the secrets of this elusive element.

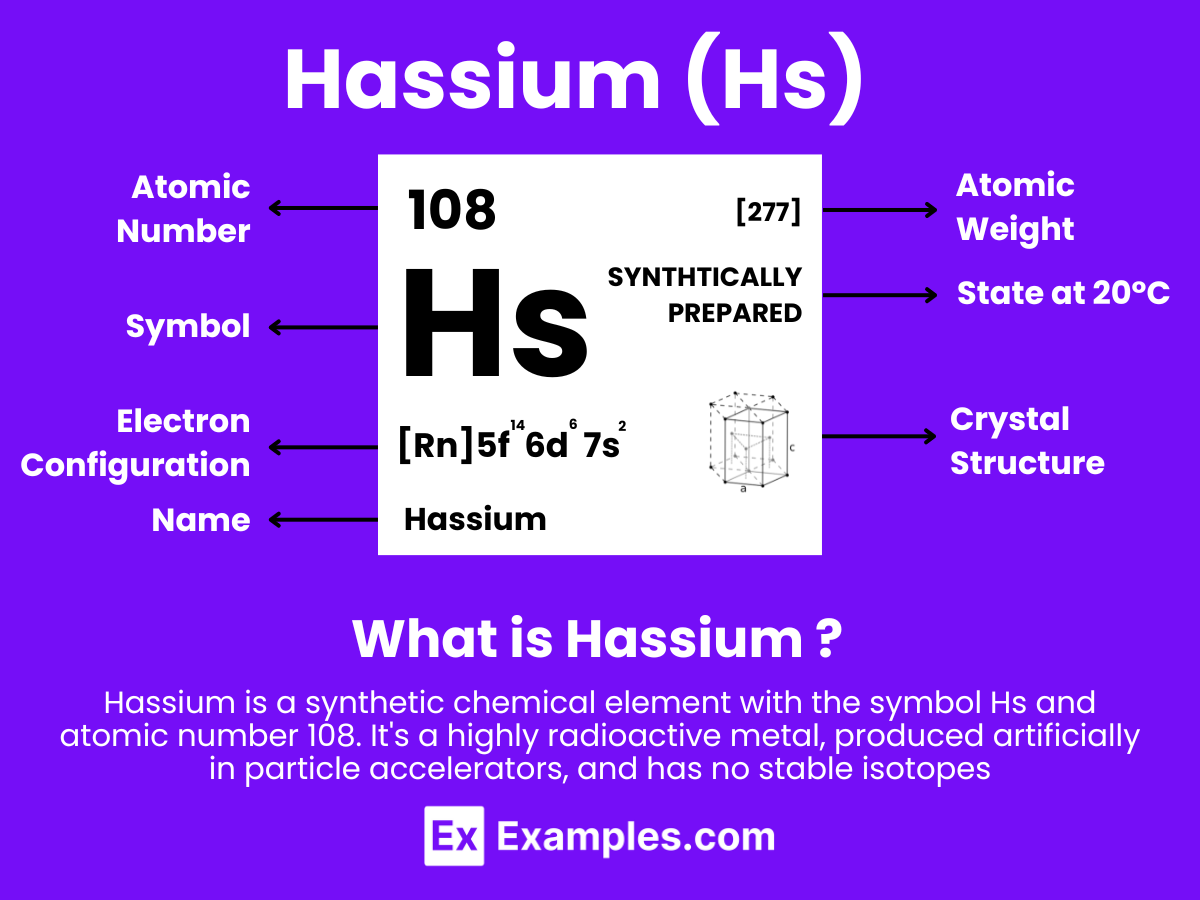

Hassium is a chemical element with the symbol Hs and atomic number 108. It is a synthetic element, and not found in nature. Hassium is produced artificially in a laboratory through the nuclear fusion of lighter atoms. Specifically, it is usually created by bombarding atoms of lead with nuclei of iron in a heavy ion accelerator.

Hassium is a member of the transactinide elements and is also part of the 7th period in the d-block of the periodic table, which means it is one of the heavy metals. Being a synthetic element, it has no significant applications outside of scientific research due to its extremely limited availability and its radioactive properties. Hassium has several isotopes, all of which are radioactive, and the most stable known isotope, hassium-277, has a half-life of approximately 11 minutes

Hassium, unlike hydrogen, is a superheavy synthetic element with distinctive characteristics, including a presumed high melting point and an unknown boiling point, indicating theoretical predictions about its phase under normal conditions are primarily speculative due to its short half-life and instability. Hassium’s behavior at the atomic and molecular levels is quite different from that of hydrogen due to its position in the periodic table as a member of the transition metals and its presumed metallic nature.

Atomic Level: Each hassium atom (Hs) contains 108 protons in its nucleus and has 108 electrons orbiting around it. The electron configuration of hassium is predicted to be [Rn] 5f¹⁴ 6d⁶ 7s², which means it has six electrons in its outermost shell that could be available for bonding, based on theoretical calculations.

Molecular Formation: In its metallic form, hassium is expected not to form molecules like H₂. Instead, if stable enough to form a solid, hassium atoms would theoretically be arranged in a crystalline lattice structure. This structure would involve the sharing of electrons between many hassium atoms in a metallic bond, which is different from the covalent bonding seen in hydrogen molecules. Due to its very short half-life and the fact that only a few atoms have ever been produced, studies on hassium’s physical and chemical properties, including its phase at various temperatures, are largely theoretical.

| Physical Property | Description of Hassium |

|---|---|

| State at 20°C | Predicted to be solid |

| Melting Point | Unknown, but predicted to be high due to its position in the periodic table |

| Boiling Point | Unknown, but similarly predicted to be high |

| Density | Estimated to be around 41 g/cm³ (predicted) |

| Appearance | Unknown, but possibly metallic and silvery in appearance (predicted) |

| Atomic Mass | [277] (Most stable isotope Hs-277, theoretical) |

The chemical properties of Hassium (Hs), like those of many superheavy elements, are largely based on theoretical calculations and predictions rather than extensive experimental data, due to its extremely short half-life and the difficulty in producing significant quantities. However, as a member of group 8 of the periodic table, Hassium is expected to exhibit chemical properties similar to its lighter homologs: iron (Fe), ruthenium (Ru), and osmium (Os). Here’s a detailed look at the anticipated chemical properties of Hassium:

Hassium is predicted to show a variety of oxidation states, with +8 being the most stable and characteristic, similar to osmium. However, oxidation states ranging from +2 to +6 may also be possible in various compounds, reflecting the versatility seen in its lighter counterparts.

The atomic and ionic radii of Hassium are expected to be comparable to those of its group 8 counterparts, adjusted for relativistic effects due to its high atomic number. This means that Hassium atoms and ions would likely be slightly smaller than those of osmium, due to the contraction of electron orbitals caused by the strong electromagnetic field of the nucleus.

While specific values for Hassium’s electronegativity and electron affinity are not precisely known, they are predicted to follow the trend seen in group 8 elements. This suggests a relatively high electronegativity, indicative of its ability to attract electrons in chemical bonds, and a positive electron affinity, suggesting it can gain electrons to form anions, although this is less likely due to its metallic nature.

| Thermodynamic Property | Value (Predicted) |

|---|---|

| Melting Point | High (Exact value unknown) |

| Boiling Point | High (Exact value unknown) |

| Heat of Fusion | Unknown |

| Heat of Vaporization | Unknown |

| Specific Heat Capacity | Unknown |

| Thermal Conductivity | Similar to osmium (Predicted) |

| Material Property | Value (Predicted) |

|---|---|

| State at 20°C | Solid |

| Density | Approx. 41 g/cm³ (Predicted) |

| Atomic Mass | 277 (Most stable isotope Hs-277) |

| Atomic Volume | Unknown |

| Electrical Conductivity | Similar to other group 8 elements (Predicted) |

| Hardness | Similar to osmium (Predicted) |

| Electromagnetic Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Electrical Conductivity | Predicted to be high, typical of metals |

| Magnetic Susceptibility | Likely to be paramagnetic or possibly diamagnetic |

| Superconductivity | Unknown, but superheavy elements typically do not exhibit superconductivity at standard conditions |

| Reflectivity | Expected to be similar to that of other heavy metals, indicating good reflectivity |

| Absorption | Predicted to absorb significant amounts of specific electromagnetic wavelengths, typical for metals |

| Permeability | Similar to other group 8 elements, likely very low due to its expected metallic nature |

| Nuclear Property | Description |

|---|---|

| Half-life | Most stable isotope (Hs-277) has a half-life of about 11 minutes |

| Decay Modes | Alpha decay primarily, with possible spontaneous fission |

| Neutron Cross Section | Theoretical, expected to be small due to the element’s large nucleus |

| Isotopes | Several isotopes synthesized, with mass numbers from 263 to 277 |

| Nuclear Spin | Theoretical predictions vary, dependent on specific isotopes |

| Nuclear Magnetic Moment | Predicted based on theoretical calculations, not directly measured |

The preparation of Hassium (Hs), element 108, involves sophisticated nuclear reactions utilizing particle accelerators. Hassium does not occur naturally and can only be created in laboratory settings by bombarding target atoms of lighter elements with accelerated particles. The most common methods for preparing Hassium involve heavy ion fusion reactions, where a lighter, projectile nucleus is accelerated to high energies and then collided with a heavier target nucleus. The general approach aims to fuse these nuclei to form a heavier nucleus, corresponding to Hassium. Here’s how Hassium has been prepared:

After the bombardment, the resultant nucleus quickly undergoes a series of decay processes. The identification of Hassium and its isotopes is achieved through the detection of these decay chains, typically involving alpha decay and spontaneous fission. Sophisticated detectors and analytical techniques are employed to track these decay events, confirming the production of Hassium.

The preparation of Hassium is highly challenging due to the need for precise control over reaction conditions, the extremely low production rates (often just a few atoms at a time), and the rapid decay of Hassium isotopes, which complicates the observation and study of its properties.

| Isotope | Half-Life | Decay Mode | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hs-263 | ~0.74 milliseconds | Alpha decay | One of the lighter isotopes, very short-lived. |

| Hs-264 | ~540 milliseconds | Alpha decay | Relatively short-lived, showcases alpha decay. |

| Hs-265 | ~2 milliseconds | Alpha decay | Offers insights into the nuclear structure. |

| Hs-266 | Data not available | Predicted alpha decay | Hypothetical isotope, not well-characterized. |

| Hs-267 | ~52 milliseconds | Alpha decay | Provides information on hassium’s alpha decay. |

| Hs-268 | ~1 second | Alpha decay, possibly spontaneous fission | Among the more stable isotopes, still short-lived. |

| Hs-269 | ~9.7 seconds | Alpha decay | Provides valuable data on heavy element decay. |

| Hs-270 | ~3.6 seconds | Alpha decay, possibly electron capture | Interesting for studies on decay processes. |

| Hs-271 | ~4 seconds | Alpha decay | Another isotope contributing to nuclear research. |

| Hs-272 | ~10 seconds | Alpha decay, spontaneous fission observed | Indicates a higher stability range. |

| Hs-277 | ~11 minutes | Alpha decay | The most stable known isotope of Hassium. |

Hassium (Hs) is a synthetic element that is produced in particle accelerators through the fusion of smaller atomic nuclei. The production process involves highly sophisticated techniques and equipment designed to overcome the repulsive forces between atomic nuclei. Here are the key steps and methods used in the production of hassium:

The applications of hassium are confined almost exclusively to the field of scientific research due to its extremely short half-life and the challenges associated with producing it in measurable quantities. Here are some of the research areas that benefit from the study of hassium:

Hassium, element 108, remains one of the most intriguing yet elusive members of the periodic table. With its theoretical properties and speculated compounds, Hassium pushes the boundaries of chemistry and physics, offering a glimpse into the behaviors of superheavy elements. Although its isotopes are short-lived and challenging to study, Hassium continues to captivate scientists, driving advancements in nuclear research and theoretical chemistry.

Text prompt

Add Tone

Production of Hassium

Applications of Hassium

What is the atomic number of hassium?

107

108

109

110

Which group in the periodic table does hassium belong to?

Group 6

Group 7

Group 8

Group 9

What is the symbol for hassium?

Hs

Ha

Ho

Hm

In which year was hassium first synthesized?

1978

1981

1984

1987

What is the most stable isotope of hassium?

Hs-270

Hs-269

Hs-277

Hs-265

Which method is used to produce hassium?

Nuclear fission

Particle accelerator collisions

Chemical vapor deposition

Electrolysis

What type of element is hassium?

Alkali metal

Lanthanide

Noble gas

Transition metal

Hassium is named after which location?

Hassium, Sweden

Hassi Messaoud, Algeria

Hasselt, Belgium

Hesse, Germany

What is the main challenge in studying hassium?

Its high toxicity

Its high reactivity

Its short half-life

Its low abundance

Which property of hassium can be predicted based on its position in the periodic table?

Color

Density

Radioactivity

Melting point

Before you leave, take our quick quiz to enhance your learning!